August 26 was Women’s Equality Day.

Cor, typical women, eh fellas? Hogging all the equality. When do we get to be equal? Never, I expect.

It is a commemoration in the USA of the day in 1920 that the vote was granted to women under the terms of the Nineteenth Amendment. Good times. 1920 seems quite late to me, but we were only a couple of years ahead of that and our Representation of the People Act 1918 was in retrospect insanely restrictive. Women could vote yes, but only if they were over thirty. And a member, or married to a member of the Local Government Register. Or if they were a graduate voting in a University constituency. It stopped short of “must also be in the possession of a penis and really, really like James Bond films”, but only just. And because James Bond films hadn’t been invented yet.

Whilst America was getting on with Women’s Equality Day, over here in the country currently known as the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland August 26 was less noble. It was the day that the Better Together campaign, who are promoting the No vote in the forthcoming Scottish independence referendum, released their advert “The woman who made up her mind”.

(Watch it here if you’re hardy.)

There was an axiom in the advertising industry in the 1980s that if you, for whatever reason, were unable to make a brilliant commercial then your next best option was to make a spine-chillingly, anatomy-wiltingly bad one. The Shake n’Vac Principle, it was known as.

Is that what Better Together are aiming for here? An infamy so grotesque that at least, after the exact details of it have faded, the name of the perpetrators will linger in the brain, maybe resulting in a few accidental votes.

The advert has been comprehensively satirised online and I don’t propose to go over all that. The hashtag #PatronisingBTLady on Twitter will take you where you need to go. The serious bottom line for Better Together is how they have failed to win over people like me.

I am their demographic. They should have been aiming at me.

Born in England, and still sounding very English, I have lived and worked in Scotland since 1992. My family and my roots still lie south of the border, but I love Scotland. I adore the way I have been allowed to become Scottish by assimilation. The people, the landscape, the culture, the political progressiveness and tendency towards equality are what have kept me in Scotland long after my original reason for moving up here disappeared.

This is my home now. I enjoy the benefits and I contribute. I feel very included.

But two years ago I was basically a No voter. I was pro-Union. My scepticism about the SNP (national socialism, hmmm, something about that phrase) had evaporated in the light of their excellent performance in the Scottish Parliament, but I still didn’t support independence. I couldn’t see the point of it.

So what has changed?

Principally I started talking to people and I started reading things from both sides of the debate and what became starkly clear almost instantly was that there is no reason – not one single reason – not to be independent.

I have listened patiently to the No arguments and I have heard nothing that isn’t fear-mongering, negative, coercive and borderline abusive bullying. It frequently contradicts itself. I am particularly amused by their argument that Scotland is somehow both a parasitic entity and a highly-valued part of the union.

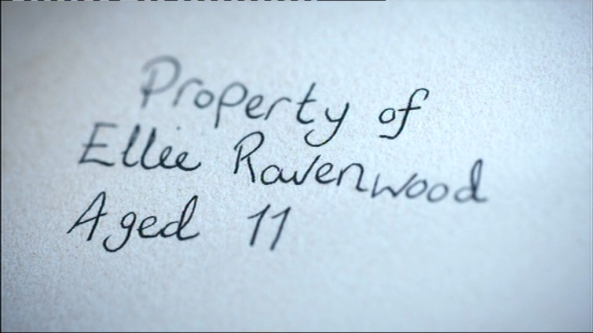

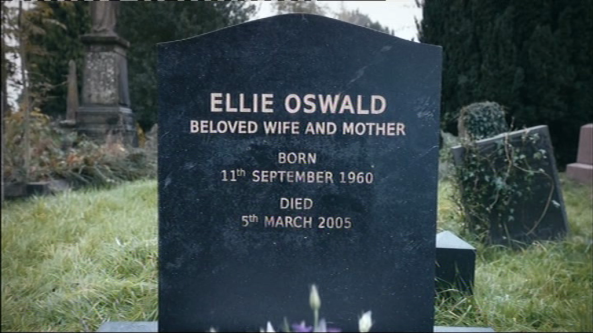

Gradually I started to become aware that the BBC, theoretically an impartial broadcaster, was showing a slant in its reporting as its own vested interests started to press down. The day before the new Doctor Who episode aired last weekend. for instance, the BBC carried a not-news story that people in Scotland would “probably” still be able to watch Doctor Who if it became an independent country.

Probably? This was at the exact same time that the show’s producers were conducting a world tour introducing Peter Capaldi and Jenna Coleman to Mexico, Brazil and Australia. Scotland is still going to be part of the world. Under what circumstances would we not be able to see Doctor Who? If there isn’t a post-independence renegotiation of publicly funded broadcasting then surely Scotland will still be free to buy in content like any other foreign market. So why was the BBC introducing a note of doubt at that point if not to destabilise and antagonise the floating voter? The thing is I don’t like being pushed around, and I suspect I am not alone.

In my experience the tone of the debate at a personal level and one-to-one on the internet has been considerate and calm. People who will be affected by the decision, whichever way it goes on September 18, understand that this is an emotional issue and that whether it’s Yes or No that finally prevails there will be a hell of a lot of repair work to do in the immediate aftermath.

The old media have been less measured unfortunately, and now that the reality of the situation looms I am beginning to see a lot of reaction from England that goes along the lines of: Well I don’t really fancy losing Scotland, I hope they vote No.

Two points here:

1) In what sense do you currently have Scotland? Don’t you think that a people’s decision (if it happens) to become self-determining should trump your vague desire to own something you don’t really seem to know too much about?

2) WE WILL STILL BE HERE! You will still be able to drive to all the people, places and things you think you like so much about us. The difference is we will be making our own decisions about how we spend our pocket money, and who we have over to stay.

When I worked in Leeds in the 1980s I travelled up to Scotland for the weekend every couple of weeks and was constantly aghast, and slightly embarrassed, at the number of times quite well-educated colleagues would ask me whether or not I needed a passport, and did I have to change my money? It’s 200 miles I would tell them. Go up and have a look. I don’t think any of them did.

But even in ignorance of the realities of Scottish life a misplaced sense of proprietorship persists. And the absurdity of it is rarely acknowledged. When David Bowie used the platform of the Brit Awards to urge Scotland to stay, the way you would talk to a scampishly disobedient pup, he was applauded. Look, said Better Together. We’ve got David Bowie and you’ve only got some bloke out of Hue & Cry.

The fact that David Bowie is an Englishman living in New York and that the bloke out of Hue & Cry was born in Scotland, lives in Scotland and has spent his life working in Scotland and therefore actually knows what he was talking about somehow slipped the media’s attention.

This is not everyone in England of course. Far from it. I have been moved by how many people have regarded Scotland with envious eyes, and have been able nonetheless to say, Go on Scotland. Fucking go for it. We would.

And that brings me to my final point.

Who wouldn’t want to be independent?

Whatever you think of Westminster, and I personally think it is at best stultified, but is more generally a cataclysmic collection of treacherous, self-interested, black-hearted, simpering Fauntleroys and cackling Harkonnens, whatever you think of it you cannot believe that is good. Nor even that it is the least bad way of doing things.

In their excellent book The Spirit Level (2009) Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett use masses of quantitative data to show over and over again that everybody benefits from a more equal society. Inequalities bring obvious disadvantages to those at the sticky end, but they make society worse for those at the affluent end too, counter-intuitively.

In the same way, the current union does nobody any favours. Scottish independence is not a threat to anyone in Scotland, quite the contrary. But also it doesn’t threaten anyone in what would remain of the UK. Without a Scottish political drag England and Wales get to express themselves much more democratically. The change, challenging though it would inevitably be, would be good for all of us.

I understand inertia. I understand resistance to change. Change is uncomfortable and scary, but that is where growth lies. Personally, socially and globally. It would be arrogant to say that the world is watching Scotland, but there are certainly parts of it that are taking an interest, and it is only when looking at the referendum from that perspective that I got my big shock.

There is nobody out there who, if placed in a similar position, would say “No thanks. I can’t be bothered.” If Scotland votes No I think there will be a lot of people internationally who will regard the country as weaker and less vigorous than they ever thought. But that isn’t important.

If Scotland votes No there will also be the difficult job of explaining to subsequent generations toiling under whatever non-devolved reforms the freshly empowered shower at Westminster bring in precisely why they did not seize the one opportunity they had to throw off the shackles. But that’s not important either.

The important thing is that the referendum offers an opportunity to be self-supporting. To be our own people rather than beholden to the shambolic blackguards who currently get to tell us what’s what.

Forget everyone else. If you have a vote look at yourself. How much responsibility are you willing to take for yourself? Some or none?