In 1997 Inverness was lovely.

People who had never visited it used to regard it with the same idle, exotic quasi-curiosity that they would Tipperary say, or Timbuktu, or a minor moon of Neptune. To be fair people who had visited Inverness basically regarded it the same way going on only to add that a moon of Neptune is slightly easier and marginally cheaper to get to. That suited us though. If we had had a town slogan at the time it would have been “Inverness! It’s probably not your sort of thing.”

1997 is the year I moved here. I came from Aberdeen, itself a pretty amazing city, and I was struck instantly and thereafter repeatedly at how civilised Inverness was. A town of between thirty and forty thousand people at the time (now sixty-two thousand) it was built around a charming historical old centre with some slightly less charming cuboid clapboard sleep-places on the upslopes of the outskirts. But this was only the start of the story, because Inverness was and is the capital of the Highlands and thus serves an area approximately the size of one and a half Belgiums or eight trillion football pitches. (Actual figures may differ.) The cultural breadth and depth was staggering.

When I bought my flat here the estate agent warned me confidentially that I might want to think twice because it was in a bit of a rough area. That was eighteen years ago. I am still in that flat and I can tell you that the crime rate is lower here than it is in Hobbiton.

It was my job that brought me to Inverness. I worked at the time for a national bookselling chain that I feel I should be coy about naming. Imagine a cross, if you can, between Roger Waters and the Rolling Stones. Yeah? Are you with me? Good. So anyway, what we used to do in the Rolling Rogers bookshop was good old, down-home, country-style retail.

Young people won’t believe this but the way it was last century was that you had a big building full of stuff that you had bought for a price. People came to your building, often from one and a half Belgiums away, and bought the stuff from you at a higher price. You made money. The producers of the stuff made money. the consumers of the stuff got their stuff.

Even at the time though, this was starting to look like a silly way of doing things. In bookselling, and in everything else-selling there were fundamentally too many people in between the content providers and the consumers. There were, in this specific example, editors, publishers, printers, distributors, lorry drivers and greedy, greedy bookshop staff all taking their cut along the way, and all slowing things down.

It was a system that couldn’t have lasted much longer than it did, particularly not once the internet started stubbornly refusing to be uninvented, but we will get on to that in a minute.

An additional problem arose from the scrapping of the Net Book Agreement in 1994. The NBA was basically resale price maintenance for books introduced in 1900. It meant that the price that was printed on a book was the price you paid wherever you bought it. This kind of mechanism seems quite egalitarian to those of us who value writing and reading. Indeed the Restrictive Practices Court agreed in 1962 when it ruled that the NBA benefited the book trade by allowing publishers to subsidise important but less commercial authors from the profits of their bestsellers. This kind of price-fixing is an anathema to the marketeers though. It churns the stomachs of the people who call books product units and who confuse cheapness with value.

As the NBA disappeared, swept away by the 1990s political attitudes to free trade, there was a momentary flush of optimism through the bookselling community, perhaps born of desperation. Hurrah, we cheered hollowly. Booksellers now have to compete in the marketplace. This can only be good news for customers who will henceforth be able to buy their books cheaper. Yay, supply and demand! Yay, the market!

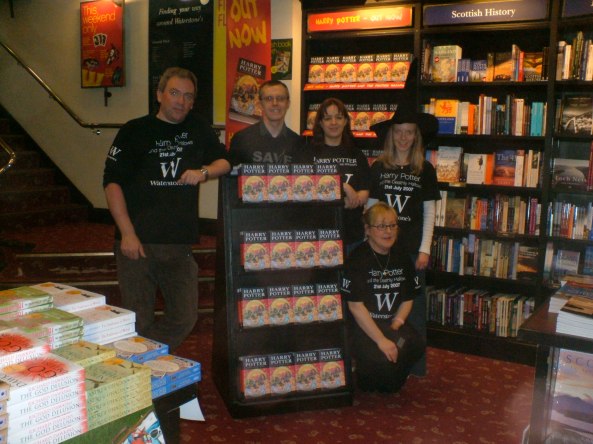

Of course what happened is that supermarkets cottoned on to using books as loss leaders and we ended up with the ridiculous situation where nobody selling any Harry Potter books made any money out of it apart from J.K. Rowling. Bookshops had to sell them at cost otherwise they wouldn’t sell any at all. And they had to maintain market share because otherwise they would lose their customers for good together with even the slightest prospect of future profit. This state of affairs reached peak absurdity during the release of the last few Harry Potter books. As Tesco stores were selling the books at below cost price it made more sense for bookshops to buy their stock from Tesco than from the publisher, and then sell them on to their own customers.

Tens of millions of pounds through the tills. Net profit, about ten pence. And they had to pay for everything out of that 10p: their booksellers, their electricity bills, their dinner of value beans on toast made from value bread, probably bought from Tesco sickeningly enough.

So bookselling was a dead trade walking even as I moved to Inverness. There were glory days though. A brief golden period when we thought that the deep range of a specialist bookseller was of more interest to a book buyer than a shallow, cheap supermarket shelf. That didn’t work though. Book buyers became accustomed to the no-profit deep-discount loss leaders in Tesco and couldn’t understand why we weren’t offering the same deal on small press poetry anthologies and niche fiction. In the blink of an eye literature became abysmally devalued.

So much for the irresistible force of the supermarkets then, but what of the other irresistible force? The internet.

Briefly in the book trade there existed the heroic but misguided notion that an informed bookseller standing behind a till would somehow be able to recommend you things better than an Amazon algorithm could. Honestly, we actually believed that for a while. And there was also the sweet conceit that a recherché form of boutique bookselling might live on as an aesthetically preferable alternative to shopping online at home in your pants. But people are people, and time is scarce, and your pants are great pants, and the internet is easy, so sadly my shop died.

That’s what happens when two irresistible forces meet a moveable, killable object.

It would have happened anyway, but it happened slightly quicker than it needed to in Inverness, and here is my understanding of how that happened.

The unchallenged assumption of everyone involved in town centre management in the early 2000s that I talked to was that Inverness was unsinkable, and who’s ever seen an iceberg anyway? Not me. I don’t think they even exist.

So whilst money was sloshing around and an ideal opportunity existed to beautify central Inverness, support local business, and consolidate its tourist attractions what actually happened was that the council left the town centre to fend for itself and chased big business instead. A huge out of town retail park was built. A twenty-four hour Tesco opened. There was a massive Borders. A Comet. A major popcorn-seller with a clutch of associated cinema screens. The people rejoiced. At least those with cars did. And lovers of bleak concrete expanses. They were pretty pleased too I imagine.

People would come in to my bookshop in the city centre to tell me how much better than us the out of town Borders was. You could buy coffee there. And newspapers. And stationery. And even books if you wanted. What the gloaters didn’t know, and what I didn’t know at the time, was that Borders were being given hugely favourable terms on their rent and rates.

We weren’t, but I’m not here to boo-hoo about that.

Inverness had a deserved reputation at that time for being riotously expensive. I remember our head office being surprised that it cost more to advertise in the Inverness Courier than it did to put the same advert in the whole of the rest of the world’s Guardian. We certainly saw that high cost reflected in our monthly outgoings. The rent and rates were dizzyingly high, the profits on the books were dismally low, and the profitability of the shop eventually dwindled to nothing at all.

Luckily booksellers are brave and mighty, and also very attractive and sexually well endowed, so we just took it on the chin. C’est la vie, we said, educatedly. Six swings and half a dozen roundabouts, innit? All’s fair in love and war. We could not compete with the big boys so we went to the wall. That’s the law of the jungle, albeit some sort of weird jungle that has walls and swings and roundabouts in it, and where everyone speaks French.

Fast forward a bit though and it transpired that Borders’ business model was not particularly robust either. That whole chain disappeared, as did Comet. Even Tesco appear slightly more strapped for cash now than they used to. The retail park currently looks grimmer than ever, and it’s always looked quite grim. It is not a place that you go to for fun, and I am left to wonder what would Inverness town centre be like now if, fifteen years ago, the investment had been made there rather than a mile up the A96.

Because Inverness city centre is a shocking mess as it stands. It’s like that chaotic, dystopian version of Hill Valley from one of the futures in Back To The Future Part II. There is an enclave of bright light and warmth in the Eastgate Shopping Centre like Elysium in that film Elysium, but it only serves to highlight how squalid the rest of town is.

There is so much deep beauty in Inverness that it makes me weep metaphorical, non-real tears at how grimy and stinking and decayed we have let it become. I used to be proud to show my home to visitors, but now I dread to think what people think the first time they step off the bus or the train.

There is an air of a place that has just let itself go. The municipal equivalent of a man alone in a bedsit living amid the detritus of fast food packages and empty bottles and cans.

In 2015 Inverness is not, in any analysis, lovely.

Ladbrokes & Paddy Power with a William Hill just over the road. Not enough choice? Worry not. There are two more branches of Brokelads just round the corner

Most of the problems are not unique to Inverness of course and I do not mean to lay all of the blame at the feet of short-sighted city centre management over a decade ago, much though I think they could have helped. In fact there is every sign now that the council are keen to renovate in the city centre where they can.

If I am going to point my blame-thrower, and I feel certain that I am, then it would be squarely in the direction of capitalism. The whole inadequate, wormy orthodoxy of capitalism. Seriously, how much longer are we going to have to pretend that the free market is the answer to everything, and that unregulated competition somehow contributes to the gaiety of nations?

I write this on the day that Ed Davey, the Lib Dem Energy Minister of this purulent government, is smearing his sneery face all over the news telling us that we are howling lunatics for not changing our energy suppliers on a monthly basis. I have paraphrased him to a degree. In doing this he is echoing the disdain of the man I had round a few weeks ago from Scottish Gas to service my gas central heating who was frankly incredulous that I bought my gas from his gas-selling organisation. His point, and Ed Davey’s, is that I could save two hundred pounds a year by paying attention to my gas supplier. Now two hundred pounds is real money. You would have to be the howling lunatic that Ed Davey didn’t quite say to turn down two hundred quid.

My point, not a good one perhaps and certainly not one I made to my gas man for reasons of personal meekness, goes roughly along the lines of I DON’T BELIEVE YOU!

My minuscule adventures in trying to change supplier for anything have resulted in a change in my personal outgoings that was basically undetectable. And it came at the cost of several hours of my time talking to pirates, wide boys and nincompoops when I could have been eating chilli, listening to Bob Mould albums and telling my partner how beautiful she is, which is very beautiful indeed seeing as you ask.

I am not the sort of person to whom two hundred pounds means nothing, but if the promise is of an imaginary two hundred pounds, and it comes at the cost of hours of my time then you know what you can take. And you’d better make it a flying one.

This multiplicity of suppliers is not a choice of wildly differing alternatives that has been given to me to benefit my life, however much it is dressed up to look like that. This is a bunch of middlemen crow-barring their way in between me the gas user and at the other end the gas supplier, all fighting for pennies and treating me like a slot machine.

I honestly liked it better when services existed to serve us rather than the other way around. I don’t want a choice of half a dozen rubbish things that are exactly the same. I want one trustworthy supplier, state regulated, that I can rely on to provide me with what I pay for and that will treat me with fairness and respect. And I know this boat has sailed, but God I pine for the days when you got your electricity from the Electricity Board and your gas from the Gas Board, and when your phone rang it was a friend or relation rather than a gobby barnacle on society’s undercarriage trying to cajole you into claiming compensation for some fictional accident or vividly-hallucinated PPI entitlement.

Now it’s all bonkers. Your electric comes from the gas people, your phone comes from the telly people and you have to download gas from the internet. No wonder everything feels so unstable all the time. We, the people who should have the power in these transactions, are concussed into submission by businesses whose model teeters on the brink of being art terrorism.

As an illustration of how wonky and skewed our economic system has become have a look at the basic retail paradigm now, as seen on the streets of Inverness and everywhere else really. It is the complete inverse of retail the way it used to be when you swapped your money for the retailer’s things. The only thing on sale in most of the shops on the High Street now is money, lovely yummy money for people who do not have any. Partly this is in the form of bookies who will sell you money for other money (at significantly disadvantageous rates it should be noted), but mostly it is in the shape of pawn-brokers or whatever we call these enterprises these days who will sell you money for things.

That’s shops now. You take the things that, like a latter day Womble, you have found. You know, the things that the everyday folk have just left lying around the insides of their houses behind locked doors in the middle of the night, and you use these things to buy money in shops.

That’s mad.

It’s nice for the people who are selling the money. they get to add a huge mark up often selling a few pence for as much as a pound, so the money tends to accrete where the money already is. But is that really sustainable? Is that a long-term model? This is not a new idea, that the rich get richer at the expense of the poor, but I have never been so aware of it. It is naked and unabashed. There is a last days of the Roman Empire shamelessness about it in fact. Grab your fiddle and your asbestos socks, and let’s see what happens next.

In an important graph that I made up whilst sitting in my economic think tank I have calculated that at some point next year there will be no money left. It will have achieved singularity and will all belong to one solitary, laughing person in the Cayman Islands.

I would like to make the following modest proposal: that we declare that person to be the WINNER OF CAPITALISM and that we allow her or him to retire gracefully, undefeated. Maybe give them a nice trophy or something from the Inverness Trophy Centre. And at that point we share all the money out equally and we start all over again, but this time with a system that is less ball-bombingly bad.

***

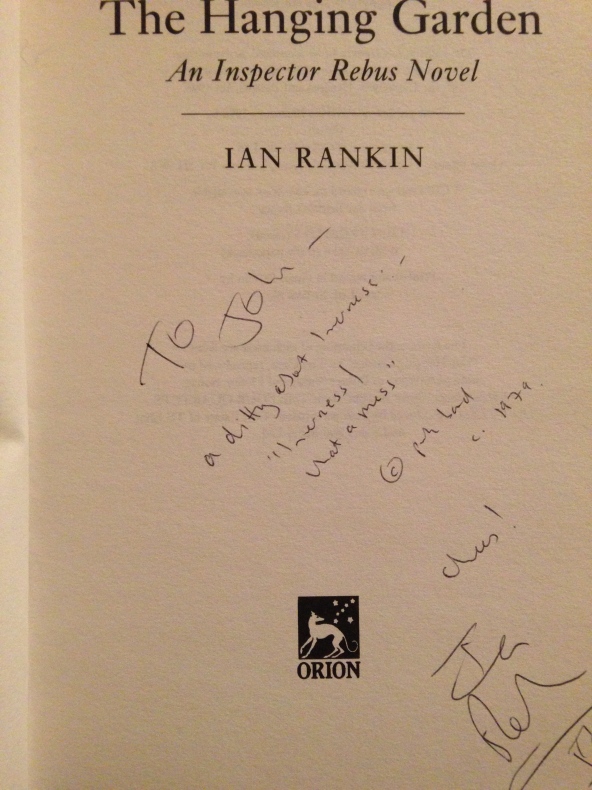

A not necessarily very interesting postscript: Ian Rankin signed a book for me not long after I moved to Inverness. In the inscription he quoted from a 1979 song by punk band The Prats: “Inverness, what a mess.”

Superb as usual John. Clear as a mountain spring.

An enjoyable but sad read.

Wonderfully funny and very sad at the same time! As you say though, John, Inverness is not unique in suffering the end of the retail sector that once existed before supermarkets took in clothes, books, electrics etc. it still has incredible beauty, the river walks and canal even if the shops are a nightmare. Its natural setting is magical. But on every word to do with capitalism I agree. The efficient market ideas and hypotheses should have died out long ago. We are probably in the throes of the death of western capitalism. And I don’t think that is exaggerating.